I consider myself pretty well informed. I read the news, I watch the press conferences, I sift through the commentators, I absorb the community feeling. I know how the emergency management arrangements generally work, I know the systems in place that can be used to talk to people and I know the pros and cons.

And yet, I am in the dark.

I’ve observed the panic buying, I’ve navigated the changing advice and rules, I’ve tried to watch dispassionately like an outer body experience or as an interested outsider the increasing fear, criticism, confusion and dissonance from people’s lived experiences and the messaging being provided by our leaders and spokespeople.

And this week I am angry.

I make no comment on whether some of the Australian States fracturing from the Federal approach is the right thing to do or not.

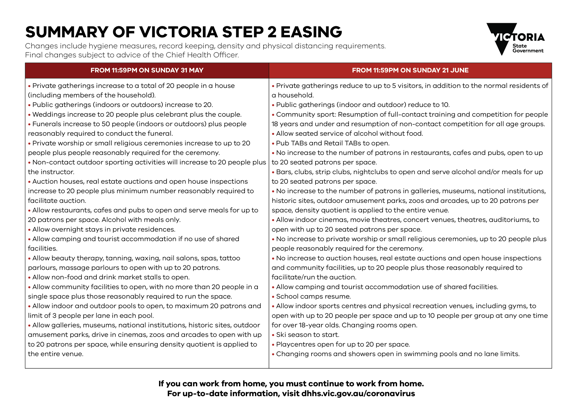

But the ‘how’ it’s being done has got me stuffed. If the idea of Victoria, NSW and QLD is at least to be responding to the gut filling anxiety some in the community are experiencing, the weekend announcements did not reduce it.

The Victorian Premier’s statement of a ‘shutdown’ of all non-essential services was strong. It was ahead of the national cabinet. It said more details to come on Monday…..

‘LOCKDOWN’ screamed the media. My local small businesses started announcing their closures because of Covid-19 on Instagram. Cafes, restaurants, hairdressers. I called my more vulnerable friends to check in, my locally travelling dad, disconnected from the social media world, to say he should head home to the farm the next day and the parents decided they would sit tight and lock the doors against the world.

I whatsapped my entire team, telling them to still proceed with their working plans Monday and we would reassess with more information when we knew exactly who and what was affected. Each conversation, I put a caveat on it that while media was saying it was going to be a ‘lockdown’, what that meant wasn’t entirely clear yet.

The PM’s defensive and late press conference on Sunday night provided some specific details about what would close and when, but did not answer all the questions.

Schools were contentious but some certainty at least in Victoria – and I heard from the PM that hairdressers didn’t have to close after all and cafes could still do takeaways (which many already were) so their Instagram and Facebook pages expressed more confusion. Did they really need to close just yet ? Should they for their own health and business good anyway?

And me : so closures and not lockdown then, I asked Twitter? Was I wrong in what I understood? Did I miss something? Twitter simply shrugged its shoulders at me with a palms up emoji.

With a continuing caveat, I whatsapped my team, because the Premier would still have more to say Monday morning.

Waking early, wondering and tired, I was confused and cranky. Looking again for the missing clarity in planning and in communicating that planning and the best community steps.

As a communicator and community member I have an opinion, like many with similar backgrounds. It’s not about throwing stones in a rapidly changing and evolving situation because I get it. This situation is a case study for crazy and as recovery community engagement specialist Anne Leadbetter observed to me separately, this situation will fill the future of PHDs and research for years to come in community behaviour change, fear and communication strategy.

But as a human being with family members, friends and team members I’m afraid to touch or breathe on, I’m needy.

The logical part of me says what I need is a more strategic plan or idea of the potential next stages, an idea of the consequences and the escalation points. What I want is rock solid, consistent, empathetic, well planned and executed, visible, responsive, coordinated response that responds to my fear and my need to control what I can in the actions I can take.

The Premier today reiterated the actions as individuals we should take, must take. But the gravity of his words are belied by the fact our shopping centres are open. Again, a dissonance, and a cacophony of other decisions being made by other States – and other countries. Tonight, I saw the first of a Victorian ad about the stage one restrictions.

New Zealand late last week implemented and communicated a four stage alert level. It appeals to my emergency management heart, and gives some comfort to me that there is an escalation point.

As our country grapples separately with decisions and NZ reaches stage three and four, my parents in a small country town are separately also holing up.

Without any more information about what’s next, they are staying home, so hopefully they won’t die.